1 in 5 Women College Rape Statistic False

Current Issues

Measuring domestic violence and sexual assault against women: a review of the literature and statistics

E-Brief: Online Only issued 6 December 2004, updated 12 December 2006

Janet Phillips, Information/E-links,

Social Policy Section

Malcolm Park, Analysis and Policy

Statistics Section

Introduction

It is very difficult to measure the true extent of violence against women as most incidences of domestic violence and sexual assault go unreported. In 2005, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Personal Safety Survey estimated that only 36 per cent of female victims of physical assault and 19 per cent of female victims of sexual assault in Australia reported the incident to police. In a briefing by the Australian Centre for the Study of Sexual Assault, What lies behind the hidden figure of sexual assault, Neame and Heenan discuss issues of prevalence and barriers to disclosure. Another report by Denise Lievore and published by the Commonwealth Office of the Status of Women (OSW) in 2003, Non-reporting and hidden recording of sexual assault: an international literature review, discusses the low level of international and Australian reporting rates and analyses the reasons behind the under-reporting.

In recent years there have been many other studies and surveys on violence against women both in Australia and internationally. This electronic brief aims to draw together major resources, research and studies on violence against women and sexual assault in Australia and a selection of the major international surveys. It complements a previous brief, Domestic Violence in Australia, issued by the Parliamentary Library in August 2003 (and updated in September 2006), which includes links to interest groups and an overview of Commonwealth government violence against women initiatives and perpetrator programs.

For some of the information in this paper, older versions of reports are still referred to even though new editions have been published. Generally this is because the newer version of the report does not include the same information as published in the older report. Some examples of this are:

- ABS, Recorded Crime Victims: The 2003 publication is the last in which national data is reported on sexual assaults. State level data is reported for 2004 and 2005 but it is not advisable to aggregate this to the national level.

- ABS, Crime and Safety: This survey was run in 2002 and 2005 but detailed data on sexual assaults is not published from the 2005 survey due to lower response rates and thus a higher uncertainty as to the accuracy of the data.

- ABS, Personal Safety Survey 2005: This publication does not include all of the level of detail published in the 1996 Women s Safety Survey, so it has not been possible to update some of the 1996 data. The ABS currently has no plans to publish more data from this survey, but it is possible to request specific pieces of information from the ABS on a consultancy basis.

Back to top

How much do we know about violence against women?

The best indicators available are from the ABS Personal Safety Survey 2005 which updates information about women s experiences of violence collected in the 1996 ABS Women s Safety Survey. The 2005 survey also includes information on men s experience of violence but unfortunately does not include all the level of detail on women as published in 1996.

From the 2005 survey the ABS estimated that in the previous 12 months:

- 363 000 women (4.7 per cent of all women) experienced physical violence; and

- 126 100 women (1.6 per cent) experienced sexual violence.

The ABS further estimated that:

- 2.56 million (33 per cent of all women) have experienced physical violence since the age of 15; and

- 1.47 million (19 per cent) have experienced sexual violence since the age of 15.

From this it is possible to estimate that approximately one in five women (19 per cent) have experienced sexual violence at some stage in their lives since the age of 15 and one in three women (33 per cent) have experienced physical violence at some stage in their lives since the age of 15.

In 2004, the ABS released Sexual Assault in Australia: a statistical overview, which provides a broad overview of sexual assault in Australia, using data from the ABS and other sources. It includes commentary to describe the prevalence and incidence of sexual assault, individual experiences, responses and outcomes and draws attention to the gaps in the data currently available. Also released in 2004 is Jenny Mouzos and Toni Makkai s Women s experiences of male violence: findings from the Australian Component of the International Violence against Women Survey (IVAWS). More information on this survey can be found in the International section of this paper.

Most sexual assault victims are female (82 per cent in 2003) and, according to the latest Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC) report, Australian Crime: Facts and Figures 2005, most sexual assaults occur at home. Of all recorded sexual assaults in Australia in 2003, 65 per cent occurred in private dwellings. These statistics, taken from ABS Recorded Crime Victims 2003 data, show that females consistently recorded higher rates of sexual assault than males irrespective of age. For females, the highest sexual assault victimisation rates are for the 10 14 and 15 19 year age groups (475 and 520 per 100 000 population); over three times the rate for the general female population and fifteen times the rate for the general male population.

For a summary and overview of other Australian research, see Judy Putt and Karl Higgins, Violence against women in Australia: key research and data issues, Australian Institute of Criminology, 1997. This report summarised the findings from the 1995 Violence Against Women Indicators Project (VAWIP), and, although it pre-dates the 1996 Women s Safety Survey, it gives a good overview of the issues.

Back to top

Is violence against women growing in Australia ?

The release of data from the ABS Personal Safety Survey 2005 has given us the opportunity for the first time in Australia to compare national rates of violence against women with comparable data from the 1996 Women s Safety Survey. Overall the survey indicated that there have been small falls in the rates of violence experienced by women in the 12 months prior to the 2005 survey when compared with the 1996 survey:

- 5.8 per cent (443 800) of women experienced violence in 2005 compared to 7.1 per cent (490 400) in 1996.

- 4.7 per cent (363 000) of women experienced physical violence in 2005, compared with 5.9 per cent (404 400) in 1996.

- The proportion of women who experienced physical assault in 2005 was 3.1 per cent (242 000) compared to 5.0 per cent (346 900) in 1996.

- Other falls were also recorded, such as small fall in the rate of sexual assaults of women, but the small numbers in the surveys on which these estimates are based mean that this fall is not statistically significant.

These small decreases have not been uniform across all groups of women though. While women under 35 experienced falls in the rate of violence they experienced in the previous 12 months, the rates for women aged 35 and over remained about the same or even increased.

Back to top

Do victims know the perpetrators?

In the ABS publication, Recorded Crime Victims 2003, 78 per cent of female victims of sexual assault knew the offender (in cases where there was sufficient data to identify the relationship of the offender to the victim). There is also a marked difference when comparing the rates of male and female victims of assault who knew their offender. Looking only at cases with sufficient data to identify the relationship, only 47 per cent of male victims of assault knew the offender while 81 per cent of female victims knew their offender in 2003.

A 2005 report released by the Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC), Homicide in Australia: 2003 2004 National Homicide Monitoring Program (NHMP) Annual Report found that:

- 36 per cent of homicide victims were female and;

- 49 per cent of female victims were killed as a result of a domestic altercation (as compared to 15 per cent of male victims).

Another AIC report released in 2003, Family Homicide in Australia, found that three-quarters of intimate partner homicides involve males killing their female partners and that the most common type of family homicide over the 13-year period was intimate partner homicide (60 per cent).

Women s experiences of male violence: findings from the Australian Component of the International Violence against Women Survey (IVAWS) includes chapters on intimate partner and non-partner violence. This survey found that over one third of women who had ever had an intimate partner (a current or previous spouse, de facto or boyfriend) experienced some form of violence by a partner in their lifetime. However, the level of violence by previous partners is much greater than that by current partners. The survey also found that 41 per cent of women had experienced violence by a non-partner male in their lifetime.

Back to top

Injuries to women in cases of sexual assault

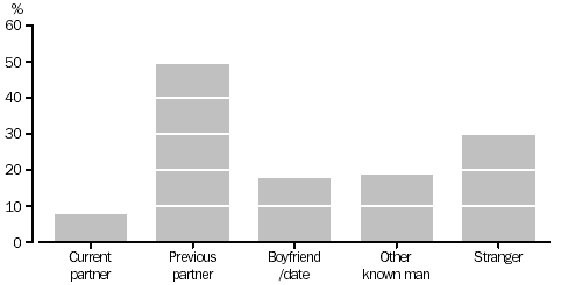

In the 2002 ABS Crime and Safety survey, 28 per cent of female victims of sexual assault reported that they had been injured in the most recent incident. The 1996 Women s Safety Survey found a similar proportion (26 per cent) of women, who had been sexually assaulted by a man since the age of 15, were physically injured in the most recent incident. The most common reported injury from the Women s Safety Survey was bruising (24 per cent) and the rate of recorded injuries varied widely depending on the relationship of the offender to the victim. Of the women who were sexually assaulted by a previous partner, 49 per cent were physically injured while 8 per cent of women sexually assaulted by their current partner were physically injured.

Women who experienced sexual assault by a man since age 15, proportion who were physically injured in most recent incident, by relationship to perpetrator, 1996

Reproduced from Sexual Assault in Australia: a statistical overview, p. 68, using data from ABS, Women s Safety Survey.

Back to top

State and territory comparisons

The ABS Personal Safety Survey 2005 includes the number and percentage of women who have experienced violence during the previous 12 months for 5 states.

Females experience of violence during the last 12 months state of residence of victim, 2005

| NSW | Vic | Qld | SA | WA | Aust(d) | |

| Physical violence(a) | ||||||

| '000 | 99.8 | 102.6 | 79.9 | 30.5 | 32.0 | 363.0 |

| % | 3.9 | 5.3 | 5.4 | 5.2 | 4.3 | 4.7 |

| Sexual violence(b) | ||||||

| '000 | 25.7 | 40.9 | 28.2 | 9.7 | 12.3 | 126.1 |

| % | 1.0 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.6 |

| Total violence(c) | ||||||

| '000 | 117.3 | 127.1 | 98.9 | 36.0 | 39.2 | 443.8 |

| % | 4.5 | 6.5 | 6.7 | 6.1 | 5.3 | 5.8 |

| No experience of violence | ||||||

| '000 | 2465.3 | 1820.5 | 1369.6 | 555.8 | 703.6 | 7249.4 |

| % | 95.5 | 93.5 | 93.3 | 93.9 | 94.7 | 94.2 |

| Total females | ||||||

| '000 | 2582.6 | 1947.6 | 1468.5 | 591.8 | 742.7 | 7693.1 |

| % | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

(a) Includes physical assault and physical threat.

(b) Includes sexual assault and sexual threat.

(c) Components may not add to total as a person may have experienced both physical and sexual violence.

(d) Includes Tas, NT and ACT.

Information is also available on sexual assaults for states and territories from the ABS publication Recorded Crime Victims 2005, though it is not broken down by the sex of the victim. The data includes a 10 year time series for each jurisdiction in Tables 9 to 16. An indexed rate is used in this state data (rather than a rate per 100 000 population) which is useful for interpreting change over time within jurisdictions. The indexed rate should not be used to make direct comparisons between states and territories though. Furthermore, care should always be taken in comparing jurisdictions crime data due to legislative, policing and data recording differences. For example, during 2003 South Australia experienced an increase in the number of sexual offences recorded, which is most likely attributable to the establishment of a Paedophile Task Force, legislation to remove pre-1983 paedophile immunity and a phone-in for sex offences committed prior to 1982.

Data is also available at the state and territory level for female victims of sexual assault from the ABS Crime and Safety 2002 publication.

Most states and territories publish more detailed information for their jurisdiction such as:

- New South Wales

- Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research Publications relating to women, domestic violence and sexual violence.

- NSW Violence Against Women Specialist Unit Strategy Reports.

- Victoria

- Victoria Police Statistics page, including Family violence by LGA 2005 06.

- Department of Justice Victorian Family Violence Database: Five Year Report.

- Queensland

- Qld Health resource pages on violence against women.

- Qld Police Service Statistical Reviews.

- South Australia

- SA Office of Crime Statistics and Research.

- Western Australia

- WA Police Facts and figures.

- Tasmania

- Women Tasmania Family and Community Violence page.

- Australian Capital Territory

- Analysis of family violence incidents: July 2003 June 2004: final report. A report prepared by the Australian Institute of Criminology for ACT Policing, Australian Federal Police

Back to top

Do victims access support services?

The ABS survey Crime and Safety 2002 indicates that 87 per cent of female victims of sexual assault accessed some form of support services after the most recent incident of assault. Up to:

- 68 per cent sought the support of a friend or colleague;

- 41 per cent sought the support of family; and

- 39 per cent sought the support of a professional or religious person.

In the 1996 Women s Safety Survey only 18 per cent of women who had experienced physical or sexual assault in the previous 12 months sought professional help after the last incident.

In 2005 the AIC published No longer silent: a study of women's help-seeking decisions and service responses to sexual assault. The report was commissioned by the Australian Government Office for Women and is based on a qualitative study of victim/survivor decision-making, their interactions with support services and the legal system and coordinated responses to adult sexual assault. Interviews were held with 36 female victim/survivors of adult sexual assault as well as counsellors and staff of sexual assault services across Australia. The report is very detailed and includes a range of recommendations focussing largely on improving social response to sexual assault and promoting organisational change.

Back to top

The criminal justice system: what are the outcomes?

We know that many crimes of violence against women are not reported to police, but what about those that are reported? Are the perpetrators identified, charged and successfully prosecuted? These are difficult questions to answer due to the different focus of the data collected about crime. For a range of reasons it is not possible to simply compare data on crimes reported by victims with criminal court data to arrive at a rate of successful offender prosecutions.

It does appear however that more women are reporting incidents of violence to police now than a decade ago. A comparison of the ABS 1996 Women s Safety Survey and Personal Safety Survey 2005 reveals that in the 12 months prior to the two survey periods:

- 36 per cent (70 400) of women who experienced physical assault by a male perpetrator reported it to the police in 2005 compared to 19 per cent (54 400) in 1996; and

- 19 per cent (19 100) of women who experienced sexual assault by a male perpetrator reported it to the police in 2005 compared to 15 per cent (14 700) in 1996.

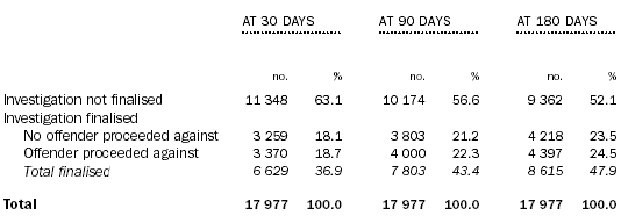

However, we know that in many cases that are reported to police the alleged offenders are not proceeded against. Data is available from the ABS on outcomes of investigations by police of reported crimes at 30, 90 and 180 days after reporting of the offence (most recently published in ABS Sexual Assault in Australia: a statistical overview, 2004). For sexual assault victims recorded in 2002, it can be seen that over half of the investigations were not finalised after 180 days. For investigations that were finalised after 180 days, just over half of them resulted in the offender being proceeded against.

Victims of sexual assault, outcome of investigation 2002

Reproduced from Sexual Assault in Australia: a statistical overview, p. 74, using data from ABS, Recorded Crime Victims.

In 2004 the Australian Institute of Criminology, commissioned by the Office of the Status of Women (OSW), produced Prosecutorial decisions in adult sexual assault cases: an Australian study. One hundred and forty one cases between 1999 and 2001 were analysed and the reasons why cases were prosecuted or withdrawn from prosecution are discussed in detail. Most of the reasons for withdrawing or proceeding were found to relate to the likelihood of securing a conviction and a key conclusion of the report is that existing prosecution policies and guidelines provide a reasonable safeguard against biased decision-making in sexual assault cases.

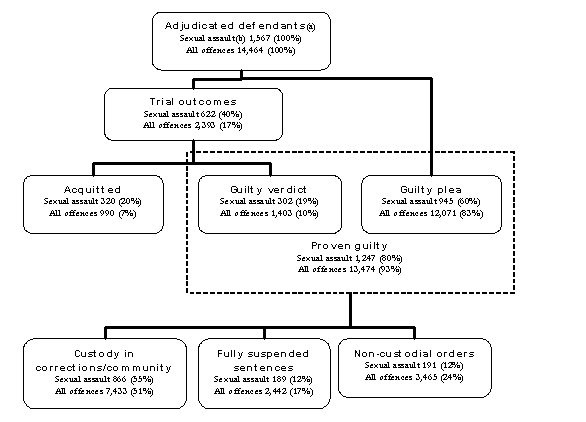

In cases that do reach the higher criminal court system, the majority (80 per cent) of defendants charged with sexual assault and related offences plead or are proven guilty. The following diagram outlines the process and outcomes of defendants charged with sexual assault and related offences that were adjudicated by higher criminal courts in 2002 03, compared with all offences. Of defendants that were proven guilty, nearly 70 per cent received a custodial sentence. The remaining 30 per cent were split equally between suspended sentences and non-custodial orders. It is worth noting that a number of sexual assault and related offences defendants (915 in 2002 03, 869 in 2003 04 and 853 in 2004 05) are adjudicated by Magistrates Criminal Courts. Magistrates Courts data are available from ABS Criminal Courts 2004 05.

Adjudicated defendants in higher criminal courts, sexual assault and related offences, Australia , 2002 03

(a) All percentages are calculated as a proportion of Adjudicated Defendants and are subject to rounding.

(b) In this diagram, all references to Sexual assault refer to the ASOC division, Sexual assault and related offences and cover the full range of offences in that division.

Reproduced from ABS, Sexual Assault in Australia: a statistical overview, p. 77, using data from ABS, Criminal Courts 2002 03.

In 2001The Attorney General s Department published a very detailed and useful report, Ending Domestic Violence? - Programmes for Perpetrators. Current responses and services in Australia and overseas are reviewed and evaluated and a range of recommendations are made.

Back to top

Women s fear of violence

Even women who have never been victims of violence are aware of their vulnerability and safety and many women feel unsafe when walking alone at night or are fearful of becoming the victims of crime. A parliamentary committee report, Inquiry into crime in the community: victims, offenders, and fear of crime, August 2004, found evidence from a variety of sources and surveys that the factor most consistently and strongly associated with fear of crime is gender. The committee also found that there is an additional dimension to fear experienced by some women which relates to domestic violence. Women are generally more fearful than men of being alone in their own homes and of walking in their neighbourhood at night. The committee found recent research confirming that women report significantly greater perceived risk and fear of crime than men, regardless of how fear of crime is measured. The committee also found that there is an additional dimension to fear experienced by some women which relates to domestic violence.

There have been various studies of women s perceptions of crime and safety such as Women s fear of violence in the community, 1999, from the Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC) and Women s Experience of Crime and Safety in Victoria from the Victorian Department of Justice, 2002. Women s fear of violence in the community found that more than 70 per cent of Australian women feel unsafe when walking alone in their area after dark and the Victorian survey found that the effects of crime and violence on women should not be underestimated. Women s differential experiences and perceptions of crime significantly affect their sense of well-being and the degree of confidence they have about their safety in their homes, at work and in the community.

The 1996 Women s Safety Survey also asked women who had experienced violence about their ongoing fear of violence and other consequences. Of women who had experienced violence by their current partner in the last 12 months, 24 per cent were currently living in fear. In comparison, 12 per cent of women who have experienced violence by their current partner at some time in the relationship (but not the last 12 months) and 11 per cent of women who experienced violence by a previous partner currently live in fear.

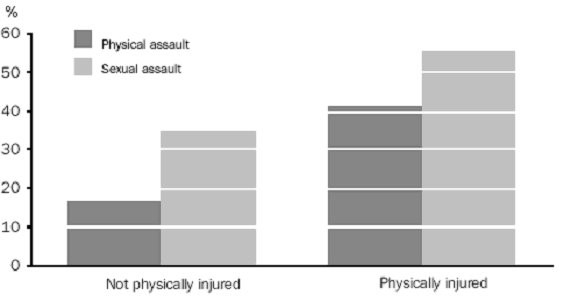

Furthermore, the 1996 Women s Safety Survey found that 30 per cent of women who had experienced a physical assault by a man reported that they had changed their day-to-day activities in the following 12 months, while 40 per cent of women who experienced a sexual assault had. Women who were physically injured were more likely to have changed their activities and social activities were most likely to have been changed.

Women who changed their day-to-day activities during the 12 months after the last incident of assault by a man, whether physically injured

Reproduced from ABS, Women s Safety Australia p. 44.

Back to top

The economic, social and health costs of violence against women

Violence against women directly affects the victims, their children, their families and friends, employers and co-workers. There can be far-reaching financial, social, health and psychological consequences. The impact of violence can also have indirect costs, including the costs to the community of bringing perpetrators to justice or the costs of medical treatment for injured victims. The following studies measure some of the economic, social and health costs.

While the human impact of domestic violence is incalculable, in a report published in 2000, Impacts and Costs of Domestic Violence on the Australian Business/Corporate Sector, staff absenteeism and replacement costs alone were estimated to cost employers over $30 million per annum while the total cost (including direct and indirect costs) to the corporate/business sector was estimated to be around $1 billion per annum.

A more recent, and very detailed, study by Access Economics, commissioned by the Office for the Status of Women (OSW), The cost of domestic violence to the Australian economy, Part 1 and Part 2, 2004, estimated that the total cost of domestic violence in 2002 03 was $8.1 billion. This estimate includes the costs of pain and suffering, health costs and long-term productivity costs.

In another study, Economic Costs of Domestic Violence, 2002, Lesley Laing and Natasha Bobic examine the relevant literature, define the terminology and compare the estimated costs of domestic violence both nationally and internationally. The value of an economic perspective, as this report demonstrates, is that it provides a powerful angle from which to view the consequences of domestic violence and to argue for social policies to improve services and support victims.

For a more general discussion of the costs of crime, including sexual assault, see Counting the costs of crime in Australia, Australian Institute of Criminology, 2003.

In 2002, the World Health Organization released a report World report on violence and health. This report examines the types of violence, including intimate partner and sexual violence, that are present worldwide and the health burden imposed by that violence.

In Australia, the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women s Health widely known as Women's Health Australia is a longitudinal population-based survey, which is examining the health of over 40 000 Australian women over a 20 year period. The publications site includes online papers or abstracts on the effects of violence on Australian women, for example Violence against young Australian women and association with reproductive events: a cross sectional analysis of a national population sample.

An Australian report on the health costs of violence against women is The health costs of violence: measuring the burden of disease caused by intimate partner violence released by VicHealth in June 2004. The report found that this form of violence is responsible for more ill-health and premature death among Victorian women under the age of 45 than any other well-known risk factors including high blood pressure, obesity and smoking. The study claims to be the first in the world to estimate the health consequences of intimate partner violence using the burden of disease methodology developed by the World Health Organization.

A paper from the Australian Domestic and Family Violence Clearinghouse website, Domestic violence and women s physical health, 2003, reviews the research identifying the short and longer-term impacts of domestic violence on women s physical health. It includes the findings of a 2000 American study showing 35 per cent of all casualty visits by women were the result of domestic violence. The health costs of violence: measuring the burden of disease caused by intimate partner violence, 2004, includes some Australian statistics on hospital admissions in Brisbane, but they refer to the sorts of injuries the women present with, not the number being admitted due to domestic violence. This report refers to a study by Gwenneth Roberts (from the Department of Psychiatry, University of Queensland) conducted at the Royal Brisbane Hospital Emergency Department from 1990 to 1993 Domestic violence victims in emergency departments. The study found that 23.3 per cent of females presenting at the Emergency Department self-reported a history of domestic violence. The results were similar to those in US studies that found one in five women presenting in emergency departments have a history of domestic violence. In a recent New Zealand study, Prevalence of intimate partner violence among women presenting to an urban adult and paediatric emergency care department, published in the New Zealand Medical Journal, 21 per cent of women screened positive for partner violence and 44 per cent reported partner violence at some time in their adulthood.

In Economic Costs of Domestic Violence, 2002, Lesley Laing and Natasha Bobic also discuss some of the indirect social and health consequences of domestic violence. For example: social and psychological consequences described for victims include anxiety, depression and other emotional distress, physical stress symptoms, suicide attempts, alcohol and drug abuse, sleep disturbances, reduced coping and problem solving skills, loss of self esteem and confidence, social isolation, fear of starting new relationships, living in fear, and other major impacts on quality of life. Immediate impacts often described for children of victims include emotional and behavioural problems, lost school time and poor school performance, adjustment problems, stress, reduced social competence, bullying and excessive cruelty to animals, running away from home, and relationship problems.

Back to top

At risk groups

Some women are more at risk of violence than others, for example, young women, children, sex workers and the homeless. For a more detailed discussion of those at risk see the 2003 briefing by the Australian Centre for the Study of Sexual Assault, What lies behind the hidden figure of sexual assault, listing research on several of these at risk groups.

Children

The ABS Personal Safety Survey 2005 asked respondents of their experience of violence before the age of 15:

- The proportion of women who experienced physical abuse before the age of 15 was 10 per cent (779 500).

- The majority of physical abuse against these young women was perpetrated by their father/step father (52.8 per cent) or mother/step mother (34.3 per cent).

- Women were more likely to have been sexually abused than men. Before the age of 15, 12 per cent (956 600) of women had been sexually abused compared to 4.5 per cent (337 400) of men.

- Only 8.6 per cent of these young women were sexually abused by strangers. Most of the abuse was perpetrated by other male relatives (35.1 per cent), father/step father (16.5 per cent), family friends (16.5 per cent) and acquaintance/neighbours (15.4 per cent).

ABS Recorded Crime Victims 2003 data shows that the highest sexual assault victimisation rates are for 10 14 and 15 19 year old females (475 and 520 per 100 000 population). For males the rates were highest for those aged 0 9 and 10 14 (90 and 88 per 100 000).

The Australian International Violence against Women Survey (IVAWS) was conducted across Australia between December 2002 and June 2003. In the Australian findings, published by the Australian Institute of Criminology in 2004, Women's experiences of male violence: findings from the Australian Component of the International Violence against Women Survey (IVAWS), statistics were collected on childhood victimisation:

- Overall, 29 per cent of women surveyed reported that they had experienced physical and/or sexual violence before the age of 16 years.

- Almost one in five experienced this abuse by parents.

- 16 per cent of women reported sexual abuse by some other person (relative or some other male).

- Women who experienced abuse during childhood were one and a half times more likely to experience any violence in adulthood.

Children are also at risk of witnessing violence. The ABS Personal Safety Survey 2005 found that 57 per cent of women who experienced violence by a current partner reported that they had children in their care at some time during the relationship, and 34 per cent said that these children had witnessed the violence. The survey also found that 40 per cent of women who experienced violence by a previous partner said that children in their care had witnessed the violence. The Australian Institute of Criminology paper Young Australians and Domestic Violence, 2001 also gives figures on children witnessing violence. This study of 5000 Australians aged between 12 and 20 found that up to one quarter of young people have witnessed physical violence against their mother or stepmother. The paper goes on to say that witnessing parental domestic violence has emerged as the strongest predictor of perpetration of violence in young people s own intimate relationships.

Another recent Australian Institute of Criminology paper, Children present in family violence incidents, 2006, analyses data collected by the Australian Capital Territory arm of the Australian Federal Police as part of the Family Violence Intervention Program. For the year 2003 04, a total of 1625 children were recorded as being present at 44 percent of family violence incidents.

In April 2000, the Office for the Status of Women as part of the Partnerships against Domestic Violence program held a conference on children, young people and domestic violence. The proceedings from the conference are to be found at The Way Forward. For other resources, the Domestic Violence and Incest Resource Centre (DVIRC) Victoria has a page on children who witness domestic violence.

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) publishes information on child protection each year, with the latest available being Child Protection Australia 2004 05. The data is collected from the community services departments of each state and territory and Australian totals are provided where that data is comparable across jurisdictions. The information presented includes notifications, investigations and substantiations of child abuse, children subject care and protection orders and children in out-of-home care. Across the range of information presented in this publication (for both boys and girls) the incidence has risen over the past 6 years, though this could be due to a better awareness of child protection concerns and an increased willingness to report such behaviour. Looking just at child abuse substantiations by sex, type of abuse and state or territory, the total number of substantiations is similar for both males and females across all the jurisdictions (being slightly higher for females in most). However, in all jurisdictions there were more substantiations of sexual abuse for females than males in 2004 05.

Indigenous children are over-represented in all categories of data presented in Child Protection Australia 2004 05.

The experiences of children have also been examined recently in an Australian Institute of Criminology paper, The Experiences of Child Complainants of Sexual Abuse in the Criminal Justice System, 2003. When asked if they would ever report sexual abuse again following their experiences in the criminal justice system, only 44 per cent of children in Queensland, 33 per cent in New South Wales and 64 per cent in Western Australia indicated that they would. The main difficulties identified by the children were waiting for the committal and trial, seeing the accused and facing cross-examination. The paper suggests that legislative and procedural reform and a more child-centred policy focus are required in order to prevent damage being done to the child by the justice system.

Pregnant women

The ABS 1996 Women s Safety Survey findings, repeated in the Year Book Australia

1998 Crime and Justice Special Article Violence against Women, found that pregnancy is a time when women may be vulnerable to abuse. The Personal Safety Survey 2005 collected the same data on violence experienced by women during pregnancy and found that of those women who experienced violence by a previous partner:

- 667 900 had been pregnant at some time during their relationship;

- 35.9 per cent of these women (239 800) experienced violence during the pregnancy; and

- for 112 000 of them (16.8 per cent) the violence occurred for the first time during the pregnancy.

A study at the pre-natal clinic of Royal Brisbane Hospital published in the Medical Journal of Australia in 1994, found that almost 30 per cent of pregnant women had a history of abuse and 8.9 per cent suffered abuse during pregnancy (Webster, J. Domestic violence in pregnancy: a prevalence study , 1994). A 2002 issues paper by A. Taft from the Australian Domestic and Family Violence Clearinghouse, Violence against women in pregnancy and after childbirth: current knowledge and issues in health care responses, outlines the issues and prevalence of violence in pregnancy in some detail.

Rural women

In 2000, the national peak body for organisations and individuals working in women s refuges, safe houses and domestic violence information/ referral services, the Women s Services Network (WESNET), produced a literature review, Domestic Violence in Regional Australia, for the Commonwealth Department of Transport and Regional Services. The report found that where comparable data exists, they indicate that there is a higher reported incidence of domestic violence in rural and remote communities than in metropolitan settings. A briefing paper, Responding to sexual assault in rural communities, from the Australian Centre for the Study of Sexual Assault in June 2004, specifically focuses on the topic of sexual assault in rural communities and, in particular, the difficulties in assessing the true extent of rural violence.

Young women

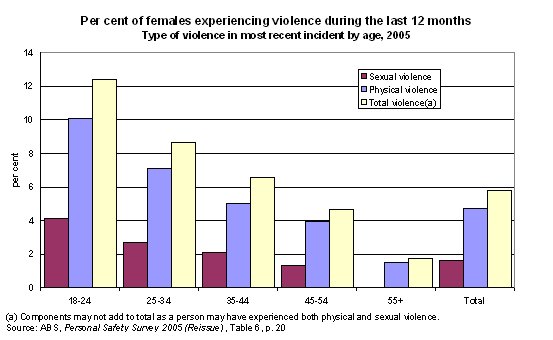

While rates of violence against young women have fallen in the past decade, as measured by the ABS 1996 Women s Safety Survey and the Personal Safety Survey 2005, women aged under 35 still experience greater levels of violence than older women.

According to the ABS publication, Recorded Crime Victims 2003, younger people (aged 24 years or less) had the greatest likelihood of being victims for all offence categories. For females, while the highest sexual assault victimisation rates were for the 10 14 and 15 19 year age groups (475 and 520 per 100 000 population), the rate for women aged 20 24 (214 per 100 000 population) is also very high.

The health costs of violence: measuring the burden of disease caused by intimate partner violence released by VicHealth in June 2004, found that domestic violence was the single biggest contributor to death, illness and disability among young women. As mentioned earlier in this brief, intimate partner violence is responsible for more ill-health and premature death among Victorian women under the age of 45 than any other well known risk factors including high blood pressure, obesity and smoking.

A recent study by the Australian Institute of Criminology, The effectiveness of legal protection in the prevention of domestic violence in the lives of young Australian women, 2000, attempts to fill some gaps in the knowledge of domestic violence against young women, and their response to it. One of the major findings of this study was that severity of violence was reduced after legal protection but the benefit was not as marked unless women sought help from the court protection orders as well as from police.

Indigenous women

Indigenous Australians are over-represented as both victims and perpetrators of all forms of violent crime in Australia.

The ABS National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey, 2002, offers the most up-to-date national statistics on the prevalence of violence in indigenous communities (and is cited in many of the reports included in this paper).

- The report shows that in 2002, one quarter of Indigenous people reported that they had been a victim of physical or threatened violence in the previous 12 months, nearly double the rate reported in 1994 (13 per cent).

- The proportion of Indigenous people who had been a victim of physical or threatened violence was similar for people living in remote and non- remote areas (23 per cent compared with 25 per cent) and for men and women (26 per cent compared with 23 per cent).

- After adjusting for age differences between the Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, comparisons from the ABS General Social Survey indicate that Indigenous people aged 18 years or over experienced double the victimisation rate of non-Indigenous people.

Family violence among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, AIHW 2006, presents information on the extent of violence (in particular family violence) in the Indigenous population, using existing surveys and administrative data collections. Information is presented on the prevalence of violence, associated harm and services for victims of violence, as well as on those in contact with the criminal justice system. The following findings are from the executive summary and more detail can be found in the full report.

- In 2003 04, 7950 Indigenous females sought refuge from the Supported Accommodation Assistance program (SAAP) to escape family violence.

- Indigenous females were 13 times more likely to seek SAAP assistance as non-Indigenous females.

- In 2003 04, there were 4500 hospitalisations of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander persons due to assault in Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory combined.

- Indigenous females were 35 times as likely to be hospitalised due to family violence-related assaults as other Australian females.

- For Indigenous females, about one in two hospitalisations for assault (50 per cent) were related to family violence compared to one in five for males.

- Most hospitalisations for family violence-related assault for females were a result of spouse or partner violence (82 per cent) compared to 38 per cent among males.

- Between 2000 and 2004, there were 150 deaths due to assault among Indigenous Australians in the four jurisdictions.

- Indigenous females were nearly ten times more likely to die due to assault as non-Indigenous females.

In July 2007 the Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision released its Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage: Key Indicators 2007. They include data, based on police records, for NSW, Victoria and WA, and discuss some of the implications of and limitations of this data and that provided by the earlier ABS 2002 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey.

In June 2006 the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission released Ending family violence and abuse in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities: key issues. The paper provides a summary of the key challenges in addressing family violence and abuse in Indigenous communities which have been identified and reported by the Commission from 2001 to 2006.

In 2004 Monique Keel wrote an Australian Institute of Family Studies briefing paper, Family violence and sexual assault in Indigenous communities: Walking the talk . It provides an overview of the key issues and findings from recent research and reports into family violence and sexual assault in indigenous communities. Another useful resource is Ch. 5 Addressing family violence in Indigenous Communities from the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (HREOC), Social Justice Report, 2003.

A paper from the National Crime Prevention Program, Violence in Indigenous communities, 2001, outlines the common forms of Indigenous family violence and estimates that the rates of death from family violence in Indigenous communities is 10.8 times higher than for the non-Indigenous population. Some remote Aboriginal communities are particularly affected by high rates of family and domestic violence. Another report by the Queensland Government released in March 2000, The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Women's Task Force on Violence Report, defines the forms of Indigenous violence, discusses the causes and makes recommendations for change. According to this report Aboriginal women in remote communities are 45 times more likely to be victims of abuse than other women.

The homicide victimisation rate is several times higher for Indigenous as compared to non-Indigenous peoples according to the Australian Institute of Criminology report, Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Homicides in Australia, 2001. From 1990 to 2000, family violence accounted for 63 per cent of all Indigenous homicides in Australia compared to 33 per cent of non-Indigenous homicides over the same decade.

The Australian Centre for the Study of Sexual Assault has a publications page specifically on Indigenous communities.

Indigenous children are over-represented in all categories of data presented in Child Protection Australia 2004 05.

Migrant women

In Double Jeopardy: Violence Against Immigrant Women in the Home, 1996, Patricia Easteal looks at the problems experienced by migrant women within the home which are made all the more difficult by isolation, cultural values and language barriers.

A recent article by Susan Rees, Human rights and the significance of psychosocial and cultural issues in domestic violence policy and intervention for refugee women , 2004, discusses some of the issues and research into violence against immigrant and refugee women.

Another article, Domestic violence and cultural and linguistic diversity, 2004, shows that women accessing supported accommodation services (SAAP) have very different requirements depending on cultural and linguistic background.

ABS data from the Women s Safety Survey 1996, Crime and Safety 2002 and Personal Safety Survey 2005, indicate that Australian-born women have a 2 3 times higher victimisation prevalence rate than women born overseas.

Women with disabilities

A literature review conducted in 2000 by Keren Howe, Violence against women with disabilities: an overview of the literature, discusses the lack of data available on women with disabilities. Some research has found, however, that women with intellectual disabilities are more likely to be abused than other women. An older study by Lesley Chenowyth, Invisible acts: violence against women with disabilities, 1993, discusses research showing that children and adults with disabilities are sexually abused and assaulted at higher rates than other people.

One US paper, Abuse and women with disabilities,1998, gives an overview of recent research, including a survey which found that 40 per cent of women with disabilities had suffered abuse or violence of some kind.

The ABS publication Sexual Assault in Australia: a statistical overview has drawn together data from the NSW Health publication, Initial Presentations to NSW Sexual Assault Service 1994 1998 and a National Association of Services Against Sexual Violence (NASASV) Report on the Snapshot Data Collection by Australian Services Against Sexual Violence, May June 2000. The data from these sources indicates that between 20 30 per cent of victims of sexual assault have some form of disability or special need. The data is further broken down by the type of disability or special need of victims.

Back to top

International crime victim and violence against women surveys

Several crime surveys have been conducted internationally in recent years that include findings on sexual assaults or violence against women. Links to the most significant of these are included below. For more detail on these and other surveys there is a good summary of the findings of several international crime victim and violence against women surveys in the appendix of Sexual violence in Australia, 2001, from the Australian Institute of Criminology.

An International Violence against Women Survey is currently in process measuring violence in ten industrialised countries. It will be a comparative survey specifically designed to target men s violence against women, especially domestic violence and sexual assault. Australia is taking part with funding from the Office for the Status of Women (OSW). In 2004 the Australian findings, published by the Australian Institute of Criminology, were released in Jenny Mouzos and Toni Makkai s Women s experiences of male violence: findings from the Australian Component of the International Violence against Women Survey (IVAWS).

The Australian International Violence against Women Survey (IVAWS) was conducted across Australia between December 2002 and June 2003. A total of 6677 women aged between 18 and 69 years participated in the survey, and provided information on their experiences of physical and sexual violence. In the past 12 months, 10 per cent of the women surveyed reported experiencing at least one incident of physical and/or sexual violence.

The latest International Crime Victims Survey (ICVS) released in 2000 by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNDOC) and the United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute (UNICRI), measured crime victimisation across seventeen industrialised countries, including Australia. Two types of sexual incidents were measured: offensive sexual behaviour and sexual assault (i.e. incidents described as rape, attempted rape or indecent assaults). Regarding sexual crime incidents, the survey found:

- For all countries combined, just over one per cent of women reported offensive sexual behaviour.

- The level was half that for sexual assaults.

- Women in Sweden, Finland, Australia and England and Wales were most at risk of sexual assault.

- Women in Japan, Northern Ireland, Poland and Portugal were least at risk.

- Many of the differences in sexual assault risks across country were small.

- Generally, the relative level of sexual assault in different countries accorded with relative levels of offensive sexual behaviour - though there were a few differences.

- Women know the offender(s) in about half of the all sexual incidents: in a third they were known by name and in about a sixth by sight. (More assaults involved offenders known by name than did incidents of offensive sexual behaviour.)

- Most sexual incidents involved only one offender.

- Weapons were very rarely involved.

The latest US National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) conducted by the United States Bureau of Justice in 2005 found that:

- Females were most often violently victimised by someone they knew (64 per cent by non-strangers) while males were more likely to be victimized by a stranger (54 per cent by strangers).

- Interestingly rape/sexual assault rates were down 69 per cent on 1993 rates.

- The decline in violent victimisation between 1993 and 2005 was experienced by persons in every demographic category considered gender, race, Hispanic origin and household income.

- The rate for rape/sexual assault in 2005 was 0.8 per 1000 aged 12 or older (a third of the 1993 rate).

The New Zealand National Survey of Crime Victims conducted in 2001 estimated that only 12 per cent of sexual victimisations were reported to the police. It also found that women, especially young women, were much more likely than men to say they had experienced sexual interference or sexual assault. Fourteen percent of women said that they had experienced sexual victimisation before the age of 17 and for some of these women, this had occurred at a very young age. A New Zealand Crime and Safety Survey was conducted in 2006 and the survey is planned to be run every two years.

New Zealand also conducted a Women s Safety Survey in 1996 which found that more than a quarter of the Maori women and a tenth of the non Maori women with current partners who participated in the Women's Safety Survey reported experiencing at least one act of physical or sexual abuse in the past 12 months. Three per cent of the women with current partners and twenty four per cent of the women with recent partners reported that they had been afraid that their partner might kill them; the comparable figures for Maori women were five per cent and forty four per cent.

A Violence against Women Survey was also conducted by Statistics Canada in 1993. It found that half of all Canadian women had experienced at least one incident of violence since the age of 16 and one in four Canadian women were victims of assault by a spouse or partner. The Statistics Canada Crime Statistics in Canada 2005 report (of police-reported crime data) found that the sexual assault rate in 2005 was 25 per cent lower than a decade ago.

Back to top

References

- Access Economics, The cost of domestic violence to the Australian economy, Part 1 and Part 2, Office for the Status of Women (OSW), 2004.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, Crime and Safety 2002.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, Criminal Courts 2002 03.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, Criminal Courts 2004 05.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey, 2002.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, Personal Safety Survey 2005 (Reissue).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, Recorded Crime Victims 2003.

NOTE: Recorded Crime Victims publications are available for 2004 and 2005, but the ABS has not published national data on assaults and sexual assaults due to differences in recording practices across jurisdictions. - Australian Bureau of Statistics, Recorded Crime Victims 2005.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, Sexual Assault in Australia: A Statistical Overview, 2004.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, Violence against Women , Australian Year Book, 1998.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, Women's Safety Australia, 1996.

- Australian Institute of Criminology, Analysis of family violence incidents: July 2003 June 2004: final report, 2006, prepared for ACT Policing, Australian Federal Police.

- Australian Institute of Criminology, Australian Crime: Facts and Figures 2005.

- Australian Institute of Criminology, Children present in family violence incidents, 2006.

- Australian Institute of Criminology, Homicide in Australia: 2003 2004 National Homicide Monitoring Program (NHMP) Annual Report, 2005.

- Australian Institute of Criminology, Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Homicides in Australia, 2001.

- Australian Institute of Criminology, No longer silent: a study of women's help-seeking decisions and service responses to sexual assault, 2005.

- Australian Institute of Criminology, Sexual violence in Australia, 2001.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Child Protection Australia 2004 05.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Family violence among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, 2006.

- Carcach, C. and Mukherjee, S., Women s fear of violence in the community, Australian Institute of Criminology, 1999.

- Chenowyth, L., Invisible acts: violence against women with disabilities, 1993.

- Department of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Policy and Development, The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Women's Task Force on Violence Report, Queensland Government report, 2000.

- Drabsch, T. Domestic Violence in NSW, NSW Parliamentary Library Research Service, 2007

- Easteal, P., Double Jeopardy: Violence Against Immigrant Women in the Home, Family Matters, no.45, Spring/Summer 1996.

- Eastwood, C., The Experiences of Child Complainants of Sexual Abuse in the Criminal Justice System, Australian Institute of Criminology Trends and Issues Paper No. 250, 2003.

- Fraser, K., Domestic violence and women's physical health, Australian Domestic and Family Violence Clearinghouse, 2003.

- Giovanetti, A. and Murdoch, F., Domestic violence and cultural and linguistic diversity, Parity, vol. 17, no. 6, July 2004.

- Henderson, M., Impacts and Costs of Domestic Violence on the Australian Business/Corporate Sector, a report to Lord Mayor's Women's Advisory Committee, Queensland, 2000.

- House Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs, Inquiry into crime in the community: victims, offenders, and fear of crime, 2004.

- Howe, K., Violence against women with disabilities: an overview of the literature, 2000.

- The Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (HREOC), Ch. 5 Addressing family violence in Indigenous Communities, in Social Justice Report, 2003.

- The Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (HREOC), Ending family violence and abuse in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities: key issues, 2006.

- Indermaur, D., Young Australians and Domestic Violence, Australian Institute of Criminology, 2001.

- Keel, M., Family violence and sexual assault in Indigenous communities: Walking the talk , 2004.

- Kolzoil-Mclain, j. et al, Prevalence of intimate partner violence among women presenting to an urban adult and paediatric emergency care department, New Zealand Medical Journal, vol. 117, no. 1206, 26 November 2004.

- Laing, L. and N. Bobic, Economic Costs of Domestic Violence, Literature Review, Australian Domestic and Family Violence Clearinghouse, 2002.

- Lee, C. (ed), Women's Health Australia: what do we know? what do we need to know? : progress on the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women's Health, 1995 2000, Women's Health Australia Research Team, 2001.

- Lievore, D., Prosecutorial decisions in adult sexual assault cases: an Australian study published by the Commonwealth Office of the Status of Women (OSW), 2004.

- Lievore, D., Non-reporting and hidden recording of sexual assault: an international literature review published by the Commonwealth Office of the Status of Women (OSW), 2003.

- Mayhew, P., Counting the costs of crime in Australia, Australian Institute of Criminology, 2003.

- McFerran, L. Taking back the castle: how Australia is making the home safer for women and children, Australian Domestic & Family Violence Clearinghouse, 2007

- Mouzos, J. and Makkai, T., Women's experiences of male violence: findings from the Australian Component of the International Violence against Women Survey (IVAWS), Australian Institute of Criminology, 2004.

- Mouzos, J. and Rushforth, M., Family Homicide in Australia, Australian Institute of Criminology, 2003.

- National Association of Services Against Sexual Violence (NASASV), Report on the Snapshot Data Collection by Australian Services Against Sexual Violence, May June 2000.

- National Crime Prevention Program, Ending Domestic Violence?: Programs for Perpetrators, Attorney General's Department, 2001.

- National Crime Prevention Program, Violence in Indigenous communities, 2001.

- Neame, A. and Heenan, M., What lies behind the hidden figure of sexual assault, Briefing No.1, Australian Centre for the Study of Sexual Assault, 2003.

- Neame, A. and Heenan, M., Responding to sexual assault in rural communities, Briefing No.3, Australian Centre for the Study of Sexual Assault, 2004.

- NSW Health, Initial Presentations to NSW Sexual Assault Service 1994 1998.

- Nosek, M. and Carol Howland, C., Abuse and women with disabilities, Violence against Women, US, 2000.

- NZ Ministry of Justice, National Survey of Crime Victims 2001 (published 2003).

- NZ Ministry of Justice, Women s Safety Survey 1996.

- Putt, J. and Higgins, K., Violence against women in Australia: key research and data issues, Australian Institute of Criminology, 1997.

- Rees, S., Human rights and the significance of psychosocial and cultural issues in domestic violence policy and intervention for refugee women , Australian Journal of Human Rights, vol. 10 no. 1, June 2004.

- Roberts, G., Domestic violence victims in emergency departments, in Chappell and Eggar (eds.) Australian violence: contemporary perspectives II, Australian Institute of Criminology, 1995.

- Statistics Canada, Violence against Women Survey, 1993.

- Statistics Canada, Crime Statistics in Canada, 2005.

- Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision, Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage: Key Indicators 2007.

- Taft A, Watson L & Lee C, Violence against young Australian women and association with reproductive events: A cross sectional analysis of a national population sample, ANZJPH, 2004; 28(4): 324 329.

- Taft, A., Violence against women in pregnancy and after childbirth: current knowledge and issues in health care responses, Australian Domestic and Family Violence Clearinghouse Issues Paper no. 6, 2002.

- UN Division for the Advancement of Women, Secretary-General s in-depth study on violence against women, 2006.

- UN Office on Drugs and Crime, International Crime Victims Survey, 2000.

- UNIFEM, Not a minute more: ending violence against women, 2003.

- US Bureau of Justice, National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), 2005.

- VicHealth, The health costs of violence: measuring the burden of disease caused by intimate partner violence Victorian Department of Health, 2004.

- Victorian Department of Justice, Women s Experience of Crime and Safety in Victoria, 2002.

- Webster, J. et al, Domestic violence in pregnancy: a prevalence study Medical Journal of Australia, vol. 161, no. 8, 1994.

- World Health Organisation, World report on violence and health, 2002.

- Women s Services Network (WESNET), Domestic Violence in Regional Australia, 2000.

- Young M, Byles J & Dobson A, The effectiveness of legal protection in the prevention of domestic violence in the lives of young Australian women, Australian Institute of Criminology trends and issues paper No. 148, 2000.

Back to top

Resource centres and key websites

- Australian Centre for the Study of Sexual Assault (ACSSA)

- Australian Domestic and Family Violence Clearinghouse

- Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC)

- Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIF)

- The Commonwealth s Women's Safety Agenda website

- Domestic and Family Violence and Sexual Assault Initiative 2007-08, a federal government funding initiative

- The Domestic Violence & Incest Resource Centre (DVIRC)

- National Crime Prevention site (Attorney General s Department)

- National Women s Justice Coalition (NWJC)

- New South Wales Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research

- Office for Women, previously the Office of the Status of Women

- United Nations Division for the Advancement of Women (DAW)

- Violence against Women (VAW) international online resources from the US Department of Justice

- Women s Services Network (WESNET)

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

Back to top

1 in 5 Women College Rape Statistic False

Source: https://www.aph.gov.au/about_parliament/parliamentary_departments/parliamentary_library/publications_archive/archive/violenceagainstwomen

0 Response to "1 in 5 Women College Rape Statistic False"

Post a Comment